One of my favorite classes in high school was typing class. I took it two years; the first year was on manual typewriters. The second year was on electric typewriters — IBM Selectrics — which were introduced by IBM in the early 1960s. Typing was a soothing, almost cathartic exercise for me, and, best of all, there was never any homework! You couldn’t take the typewriters home to practice. I was a straight A student.

I had no idea at the time how significantly those typing classes would benefit me the rest of my life. I put them right to work, typing term papers for fellow students in college to earn a few extra bucks. And by the time computers came along, my touch-typing skills were critical to my success in several ways, not the least of which was typesetting for my printing business starting in the mid-1980s.

So, I’ve been fascinated with keyboards practically all my life. Not so much the manual typewriter keyboards I learned on, but that Selectric keyboard — the clack-clack-clack from typing rhythmically — I loved that sound. And, of course, I was fascinated with the technology that translated my keystrokes to that little golf-ball-sized sphere covered with all the characters of the keyboard and placed them perfectly on a sheet of letterhead.

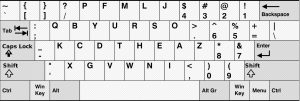

I learned to type on the QWERTY keyboard layout, as did almost everyone else. The QWERTY layout, introduced in the 1870s, was specifically designed to slow typists down back in the early days of the manual typewriter so that they didn’t jam the individual type bars as they rose to strike the ribbon. It required you to use some of your weakest fingers for often used keys — typing the “a” with your left pinky, for instance.

By the time the Selectric typewriter came along, that no longer mattered. You could no longer jam the type bars, no matter how fast you typed because there weren’t any. But we’d all already learned the QWERTY layout, and the typewriter manufacturers weren’t too interested in producing a different layout for which everyone would have to learn to type again from scratch. So to this day, QWERTY has remained the standard.

However, there is a better way! In 1936, Dr. August Dvorak introduced his keyboard layout, known now as the Dvorak keyboard, scientifically laid out to make it easier and faster to type. It placed 70% of the most commonly used keystrokes on the home row of the keyboard (compared to only 50% on the QWERTY keyboard), reducing fatigue and nearly doubling the typing speed of the average typist. Still, it was an uphill battle, and only a small percentage of typists use the Dvorak keyboard layout today, even though it’s more readily available than ever before.

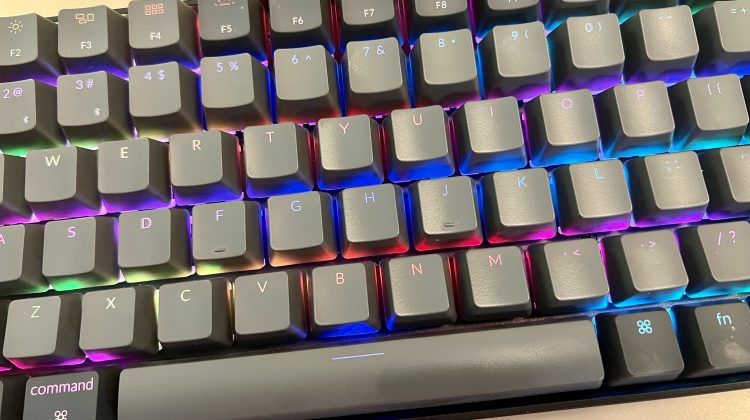

Keyboards have once again been on my mind the last several weeks. I’d been looking into the idea of purchasing a mechanical keyboard for use at my desk with my Mac. Keyboards these days come in two “flavors” — membrane keyboards, such as you’ll find on laptops and most low-profile computer keyboards, and mechanical keyboards, a throwback to older keyboards even all the way back to that IBM Selectric. On a membrane keyboard, each key presses into a silicone bubble over a switch that sends the signal for the appropriate letter to the computer. They typically have very shallow key travel and can be more tiring to use for a lot of typing. Mechanical keyboards have much greater key travel and use springs in each key to provide some resistance to your fingers and push your finger back off the key after the computer registers your keystroke. That’s an oversimplification of the two types — there are many variations of each of them — but I won’t go into that here. To most people, the significant differences are noise and typing speed/accuracy. Membrane keyboards tend to be quiet, while mechanical keyboards are clicky and have a very different feel. Some people argue that you can type much faster and more accurately on a mechanical keyboard, but there is very little if any evidence for that.

I purchased a Keychron K2 mechanical keyboard about a month ago and quickly fell in love with it. There is a learning curve if you haven’t used a mechanical keyboard in a long time, but for me, it was relatively short. With the auditory feedback of the clicky keys, and the increased key travel as you type, I think — at least it feels like — I’m typing faster and more accurately than ever. But that’s not the most important thing. Typing is once again a pleasure. I eagerly look forward to sitting down at my desk to push those mechanical keys. I’m inspired to type, inspired to write again. And that’s really the most significant thing about using a mechanical keyboard for me. No, I probably can’t type faster than you. But I might be having more fun doing it than you!

The Keychron K2 is a smaller keyboard because it has no numeric keypad. I liked the reclaimed desk space. But after several weeks of using it, I missed the numeric keypad more than I expected. So, I returned it and bought the Keychron K4 instead, which is still smaller than a traditional full extended keyboard, but it does have a numeric keypad. Me — happy.

And one final thought. Many mechanical keyboards can be highly customized — different keycaps, different switches, different lighting under the keys, different key materials, and keystrokes can be reassigned. That translates to a Yay for Dvorak! Almost any mechanical keyboard can be reconfigured with the Dvorak layout with a new set of keycaps, which are relatively inexpensive, and software to remap the keystrokes. I may be too old at this point to be willing to take the time to learn the Dvorak layout, especially since I’m quite proficient on the QWERTY layout, but it sure is nice to know the option is there.